Global obesity is on the rise

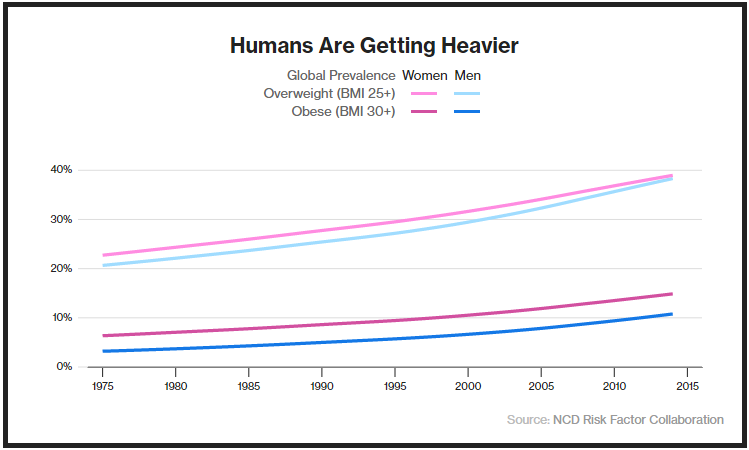

Humanity is putting on weight. Across the globe, in wealthy countries and developing nations, among children and adults, an increasing number of people are overweight or obese. Today, nearly 40 percent of the world’s adults fall into one of those categories, according to new estimates by a global network of researchers called the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration.

Economic forces are conspiring to cause the great global weight gain. Countries grow wealthier and increase consumption. People move from rural areas to cities, where they have ready access to inexpensive, processed foods. Machines do work that humans once did, decreasing the amount of energy people use. And global trade means the reach of junk food has never been greater. Up against these trends, no country has figured out how to reverse the rise of obesity.

In 2014, there were 114 countries where more than half the adult population was considered overweight, including much of the Americas, Europe, and the Middle East, according to World Health Organization data. In small Pacific Island nations and Persian Gulf states, more than two-thirds of the population is considered overweight or obese, a higher prevalence than in the United States.

Researchers estimate that excess weight caused 3.4 million deaths worldwide in 2010. Being overweight or obese is a risk factor for chronic conditions like cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Those are rising worldwide, too. There were an estimated 422 million adults with diabetes in 2014, a rate of 8.5 percent, compared to 4.7 percent in 1980, according to new estimates published by the World Health Organization April 6.

Diabetes is rising fastest in low- and middle-income countries. It’s most common in the region that includes the Middle East and North Africa, where levels of physical inactivity are high.

The number of people who are overweight or obese is going up pretty much everywhere. The world has made progress against health threats from smoking and malnutrition to malaria and waterborne illnesses. No country has yet reversed the obesity epidemic. “Not only is obesity increasing, but no national success stories have been reported in the past 33 years,” researchers in the Lancet wrote in a 2014 report funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

A United Nations plan published in 2013 calls for halting the rise in diabetes and obesity by 2025. Though the pace of increase has slowed in some places, Lancet researchers recently called the chances of the world meeting that target “virtually zero.”

So what’s causing obesity?

The causes of the worldwide weight gain are complicated, and the story is different from country to country. There are some common trends: Rising incomes, global trade, changing food supplies, and declines in physical activity all contribute.

The world has a lot more food than it once did. For most of history, humans struggled to get enough to eat. Now, in many countries, the food supply is more than sufficient to provide the energy people need. It’s difficult to measure how much people actually eat, but estimates of the calories available for consumption show they’ve steadily climbed over the past half century.

That transformation has unquestionable benefits, with millions of people avoiding starvation and malnutrition. But the increase in obesity, diabetes, and other chronic diseases indicates that too much food —and less healthful food, especially— can have harmful effects on a population as well.

How we use the energy we get from food has also shifted. Humans were hunter-gatherers until the beginning of agriculture more than 10,000 years ago. Even in wealthy countries, most people are only a few generations removed from ancestors who worked in the fields.

Today, the majority of humanity lives in cities. Work, play, and transit involve less physical activity than they did in an era before computers, televisions, and cars. Globally, almost one-third of adults don’t get the recommended level of physical activity, according to research published in 2012.

There may be other factors that we don’t fully understand, such as genetics, changes to humans’ gut bacteria, or chemicals in the environment that influence our metabolism.

What can be done about obesity?

Increased food availability, growing global wealth, and urbanization are likely to continue. In the United States, obesity plateaued in the first decade of the 21st century, and among the youngest children it may be decreasing. To turn the trend around, Mexico began taxing sugary beverages in 2014, with early indicators showing soda sales declining.

With obesity trends intertwined with economic forces, some advocates say that health considerationsneed to be written into trade and economic policies, like the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The trade deal, currently being considered by 12 nations, including Japan, Australia, Mexico, Canada, and the United States, would lower tariffs on food products like meat, dairy, and sugar, potentially increasing the availability of cheap food.

The trade agreement could also empower corporations to challenge governments’ attempts to fight obesity through food labeling laws or subsidies for more nutritious goods.

The course of the obesity epidemic won’t rest on the TPP alone. But it might depend on how well countries can balance the health of their people with the global forces shaping their economies.